As a casual student of Chinese mythology (learned mostly from Japanese anime, perhaps not the most reliable source) I was very excited to see this book land on our shelves. It is the newest translation of one of the oldest collections of legends in history, written by Wu Cheng’en (probably) and first published in China in 1562. Its original title was Hsi-Yu-Chi (Saiyuki) or Journey to the West. It is a record of the myths that accumulated around an actual historical journey, by a monk named Xuanzang who walked from China to India to collect Buddhist wisdom in 629 AD. The sixteen-year journey seemingly inspired a lot of stories—Wu Cheng’en’s original novel requires three volumes.

The historical Xuanzang was probably not accompanied and protected on his journey by three outcast immortal demons, one of which was the Monkey King. But in Wu Cheng’en’s version of the tale, Monkey is a lot more interesting than the holy monk, who doesn’t even show up until Chapter Nine or so. A few chapters later, shortly after embarking upon his journey to India, Xuanzang releases Monkey from a (well-deserved) 500-year captivity. The other two demons, seeking their own redemption, join in subsequent chapters. But Monkey is the hero of this story.

Most fantasy readers have heard of the Monkey King, even if they don’t know about Hsi-Yu-Chi. He has been the star of movies, manga and anime, usually under the name Son Goku or Sun Wukong. His magic enlargeable staff is the seed of all those weapons that appear out of nowhere, and his ability to create fighting clones of himself is a key video game and anime trope. Clearly the prototype for shonen characters like Naruto, Monkey is mischievous, heedless, over-confident, and clever. He can also be selfishly cruel, sometimes becoming a trickster figure similar to Loki. But his enthusiasm and passion remain irrepressible—an indestructible, powerful, eternally fourteen-year-old kid.

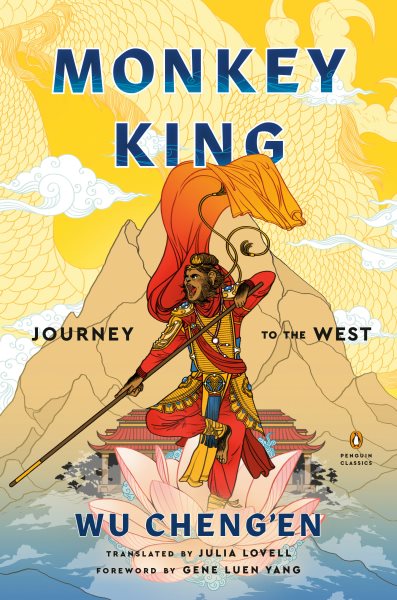

This current translation, titled Monkey King: Journey to the West, is by Julia Lovell, a “professor of modern China” at the University of London. At only 339 pages, it is most definitely an abridgement of the original. (The details are explained in the scholarly introduction, with footnotes, of course.) Lovell’s translation is easy to read, with modern language and a great feel for both the ridiculousness and high adventure inherent in the story. I have not read all of it yet, but would begin reading it out loud at once, if I still had a kid at home to read it to. I might consider skipping a few of the more questionable phrases, though. That Monkey does not hold back any words or feelings.

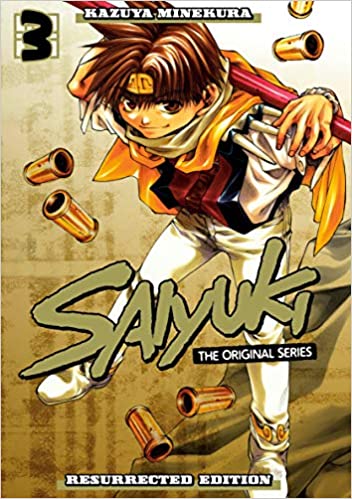

The last image is of Son Goku on the cover of my favorite anime/manga about the Journey to the West. For my review, go to twincitiesgeek.com, and search “Saiyuki.”

The post A New Translation of Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en appeared first on DreamHaven.